By Jared Davidson – Archivist

Mail, telegrams, pamphlets and books, news and newspapers, plays, photographs, films, and speech were all subject to censorship – or restrictions – during the First World War. Modelled along British lines, censorship was designed to stop information like troop movements from falling into enemy hands. But it quickly became a way for those in power to strengthen their control during a potentially turbulent time. By the war’s end, censorship in New Zealand had targeted anyone who threatened the war effort, the economy, or the state itself, while censorship at the front meant the grim reality of war was little-known at home.

Several laws censoring printed material had been introduced in the two decades preceding the First World War, and the development of cinema in the 1900s also led to film censorship laws. However the First World War marked a turning point in the history of censorship and state control. The war was more than a conflict of armies, it was seen as a conflict of societies, and failure on the home front could lead to defeat on the battlefront. Public opinion gained a new significance. At the same time, advances in technology and the development of a centralised postal service meant controlling communications could be achieved relatively easily. This saw the censorship of all forms of communication, restrictions placed on movement (the modern passport was born in 1916), and a myriad of war regulations controlling what could or couldn’t be expressed. The military also enforced censorship and racial segregation in the former German colony of Samoa, which New Zealand occupied in August 1914.

The mail sorting room in Wellington's General Post Office, circa 1920. Image courtesy of Archives New Zealand.

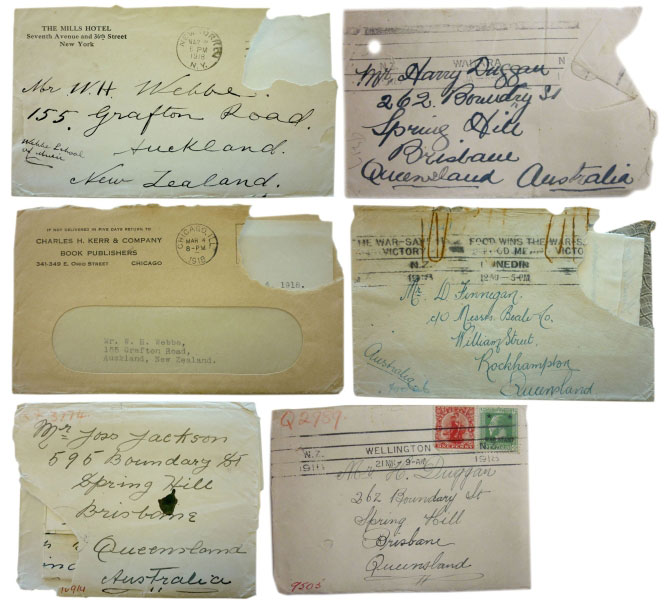

Some of the domestic and international correspondence that was censored in the First World War. Image courtesy of Archives New Zealand.

News of military campaigns was already heavily censored by the time it reached New Zealand, but information about local military activity and shipping movements – which would normally be reported in the newspapers – was also restricted. From July 1918 the Chief Censor could order newspaper editors to submit their entire publication to him before it was printed.

Battlefront accounts were heavily censored to portray the British cause in the best possible light. Soldiers’ letters were also censored by officers at the front, especially after the New Zealand Division landed in Europe in early 1916. Responsibility for censoring letters lay with company commanders, who usually had more pressing concerns and delegated the task to junior officers. Chaplains also did duty as censors, which probably encouraged self-censorship.

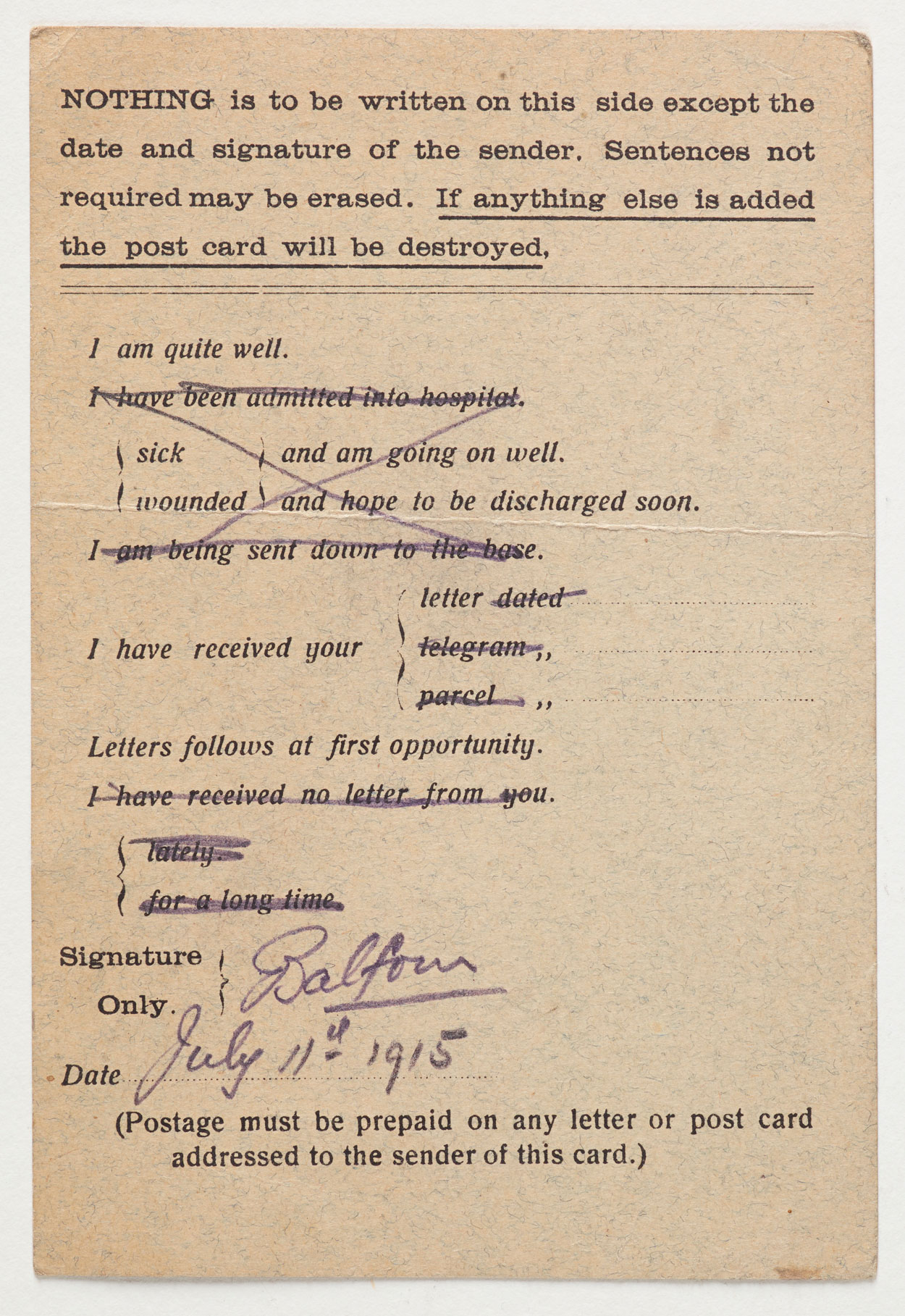

Field service postcards like this allowed censors to approve correspondence from soliders more quickly. Instead of writing a letter, they would choose the most fitting statement from each option and cross out the rest. Image courtesy of Te Papa, ref: PH000709/35.

Domestic mail was stopped, opened, and searched for any breaches of censorship laws or hints of disloyalty. Publications that caused ‘hostility and ill-will between different classes of His Majesty’s subjects’ were banned, such as the Irish Republican Green Ray or the revolutionary syndicalist Direct Action. It was illegal to screen any film that had not been approved by a government censor. Gender and sexual norms were policed. Seditious utterances, a category of elastic dimensions in the hands of the state, became an offence, and anyone whispering, writing or distributing such intentions faced prosecution.

Those convicted of sharing information useful to the enemy, such as harbour reports, were fined up to £10, yet anyone who criticised the actions of the government were fined £100 (close to $20,000 in today’s money) or were imprisoned for 12 months with hard labour. By November 1918, 287 people had been charged or jailed for seditious or disloyal remarks. Per capita, this was far greater than Britain, where 422 people of a population of over 42 million were convicted or jailed for sedition.

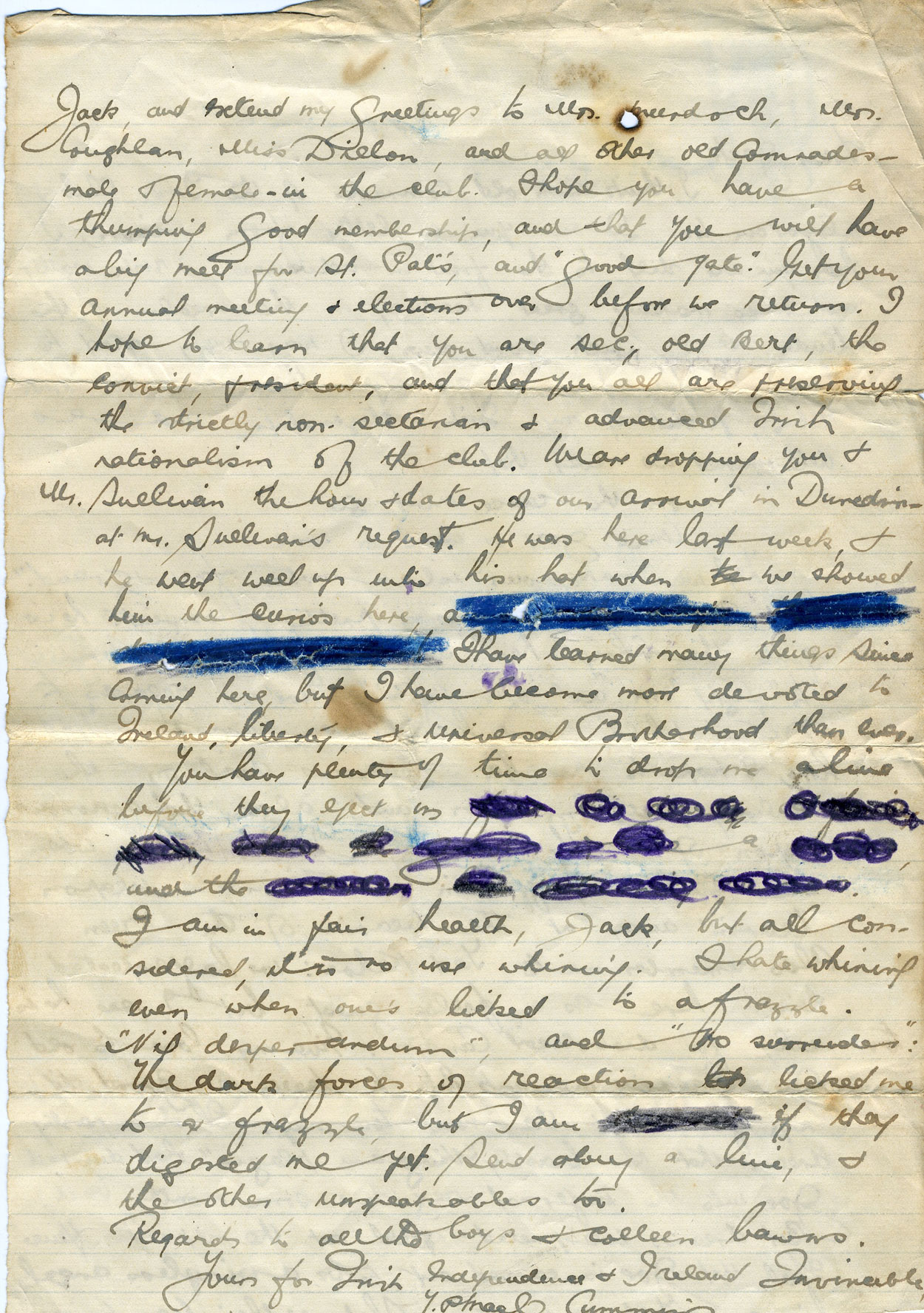

The mail of prisoners in New Zealand were subjected to heavy censorship. After the editor of Green Ray, Tom Cummings, was arrested for his Irish Republican views in 1918, his prison letters were censored. Image courtesy of Seán Brosnahan.

Solicitor General Sir John Salmond believed such wartime powers heralded ‘a constitutional revolution’ but that ’despotic government was valid in times of national emergency.’ Postal censor Walter Tanner argued that ‘in times of danger to the State, when individuals or societies are reasonably believed to be acting against the safety of the State, an examination of internal correspondence is fully justified.’ Most people agreed. Despite a dissident minority and broader unrest over inflation and conscription in the latter years of the war, the population generally consented to wartime polices and tolerated increased censorship and surveillance.

However the state’s intrusion into people’s private thoughts and opinions had material and long-lasting effects. Writers critical of the government had their mail or books detained, were put under close surveillance, or had their homes or offices raided. Some were jailed. Others were deported. This work, and the red scare of the post-war years, saw the birth of official state surveillance in 1919. Other wartime powers were extended into peacetime: the 1920 War Regulations Continuation Act was not revoked until 1947. As a result, the First World War strengthened the state’s ability to surveille its populace in times of crisis for years to come.

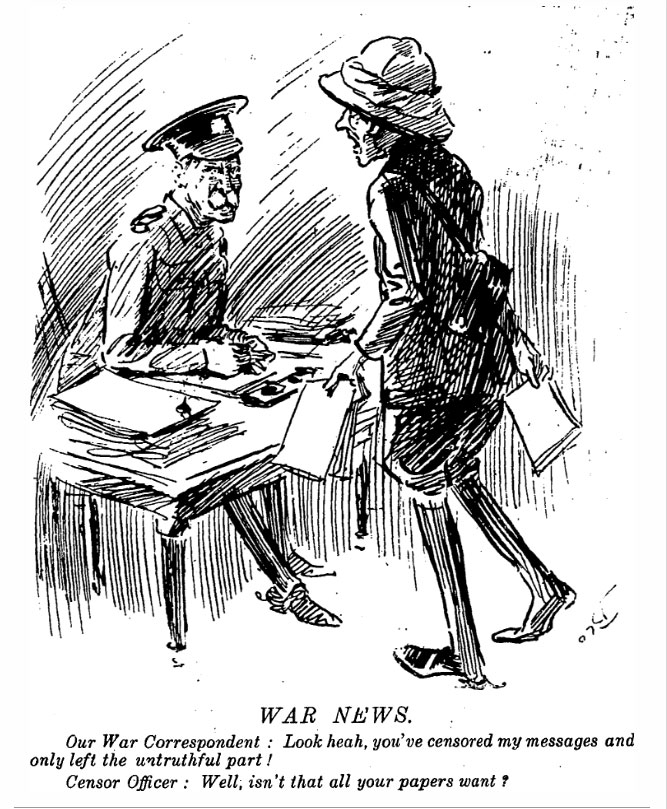

This cartoon from the 4 March 1916 issue of Observer makes a comment about the perceived thruthfulness of news in war. Image courtesy of National Library of New Zealand.

Read more perspectives on censorship at WW100.govt.nz/censorship